One of my favorites things about my job as a marketing and communications officer for a language school in the Zona Maya is apprising visiting students of the fact that the Maya aren’t dead.

It’s not something I do straight out.

When I take a group on a walking tour, I explain that our town, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, is in the heart of the Zona Maya, where the Maya people fought off the Spanish and then held out the longest against incorporation into Mexico, some until the 1940s.

I’ll point out a traditional house made of vertical poles with a thatch roof and explain that Maya families have lived in similar houses for thousands of years. I share that many people here consider themselves Maya first and Mexican second—a lot of locals speak Maya as their first or only language.

The students will nod politely, usually quietly. And then about 20 minutes into the tour, someone will say sheepishly: “Maybe this sounds silly, but … I didn’t know the Maya were still alive.”

I’m never holier than thou about this comment. The truth is, I didn’t know how very much alive the Maya were until I moved here one year ago.

Originally I was embarrassed. How on earth could I have moved to the Zona Maya to work in a school that offers Maya without knowing about the Maya?

I thought I did know about the Maya. I knew about the pyramids and the chac mools and the deities and the ritual sacrifice. I knew that I could go visit ruins at Tulum and Chichen Itza. I knew the Maya had predicted the world would end in 2012. These were things I knew—that everybody knew—about the Maya.

And then I got here and my landlord’s electrician began to give me impromptu Maya lessons. “Ba’ax ka wa’alik,” he’d say and then translate into Spanish “Que tal.” I learned that our local hot dog joint had a Maya name and not in a particularly kitschy way, Nohoch Pek (“big dog”). I noticed that the vast majority of our students—kids in baseball caps and “One Direction” tshirts—had abrupt surnames like Puc and Ek.

For a while I absorbed these details much as I see our new students doing—quietly but with confusion, and a bit of a mental barrier. Surely this information taken in total meant that there was a strong Maya heritage here, that in this small town, these lovely people were simply the descendants of the ancient great civilization.

But then I began to notice how many people around town were speaking Maya—a beautiful, soft language that floats up and down on the vowels and has a slight click in the back of the throat. I’d ask a young student if she spoke Maya and she’d say “No … but my mom does and I understand it.”

And I thought to myself, Now wait a minute…

At this point I’ve moved away from being embarrassed. This year I’ve learned that uncomfortable cluelessness is just part of immersing in a new language and culture; embarrassment gets in the way of getting to the good stuff, the part where oh, I don’t know, your entire worldview changes.

I’ve spent a lot of time since my initial reckoning learning about the modern Maya, and thinking about what might be to blame for the communal misconception about their being alive. Here’s what I’ve come up with:

History books and more recently, the internet. Here’s an example of what you come across when you look up information the Maya: “The Maya were a mysterious ancient civilization with advanced writing, mathematics and astronomical systems, and whose predictions linger in todays headlines.” This sentence is an introduction to an approximately 1,600 word piece I found online describing a timeline for Maya civilization. The piece wraps up by talking about the decline of the Maya in the 8th and 9th centuries. The last 78 words mention that the Maya are still alive.

Mel Gibson. The film “Apocalypto”. It’s purportedly about the ancient Maya but none of the people playing the Maya are Maya (you can tell by their extreme tallness, as the Maya are very short). Also, everyone is running through the jungle semi-naked which the modern Maya very rarely do. The point is that if you were using this film as a way of identifying the modern Maya, it would be mostly unhelpful.

The Spanish. They did everything in their power to eradicate the Maya. When you go to places like Valladolid and Merida in the Yucatán peninsula, you see handsome colonial buildings constructed on a base of stone taken from the Maya buildings they destroyed. The predominant language of the Mexico is obviously not Maya.

The Maya. Yes, the Maya, though I don’t put them in the blame category. One of the unfortunate things about being an oppressed people is that it gets to you. The kids in the “One Direction” shirts often don’t speak Maya though their parents or grandparents did, or just won’t tell you that they do.

The reason I have gleaned over the course of this year from talking to people in this community is that speaking Maya has unfortunately become associated with being backwoods or uneducated. Parents who want their kids to go to university and get a well-paid job are not necessarily interested in passing down a language that won’t help their kids achieve those things.

The desire to give tourists what they want. The tourists want to see the pyramids so that’s what the tour guides talk about. The weird thing is that if you’re paying attention, you’ll notice that many of the guides, when they stop speaking to their groups in English or Spanish (or French or Italian or German) will speak Maya to each other. It’s rare that tourists recognize that actual Maya people are right in front of them.

I think it would be great if the guides would go on to tell the rest of the story, the part that bridges those pyramids to themselves. It’s not entirely a happy tale, but it’s one that I find to be a remarkable account of resilience. I think it would both go along way toward eradicating the belief that the Maya are dead and, once that sticky wicket was out of the way, make the tourists understand just how impressive the modern Maya are.

For me the story of the modern Maya starts where the tour guides tend to end, with the collapse of Maya civilization. True, that happened. But also true: not everybody died. The Maya were still here when the Spanish arrived in the 1500s and spent the next several hundred years intermittently enslaved on their own lands and fighting for independence.

In the 1800s—in the wake of Mexico’s liberation from Spain—they made an extraordinary attempt for freedom that almost worked. During the Caste War they fought off the Spanish-descended ruling class and in my area, formed the independent state of Chan Santa Cruz (it was even recognized by the British for a while). Though the war technically ended in 1901, Maya resistance continued in the unforgiving jungle into the 1940s and by some accounts, into the ’50s.

Ultimately, the Maya didn’t exactly win. But they also never entirely capitulated, and that I find fascinating. The area that was Chan Santa Cruz—home to much of the Mayan Riviera, as well as Felipe Carrillo Puerto—didn’t even become a state until 1974.

And it’s for damn sure the Maya didn’t disappear. Nearly one million people speak Yucatec Maya today (often just called “Maya”), and 6 million people between Mexico, Guatemala and Belize speak one of about 30 Mayan languages.

As further proof that the Maya are not dead, this past weekend I spent an hour and a half on a bus ride receiving a Maya lesson from a lovely older gentleman who was from a community in Yucatán. This guy is just one of the many incredibly nice Maya people I have met since I’ve lived here. My overall impression has been that the Maya are generous and warm and more than willing to tell you about their language and culture if you ask.

The older generation tends toward traditional clothing, the women often in huipiles (white cotton dresses with hand-embroidered flowers at the chest and hem) and the men in loose, cuffed pants and chanclas (like flip flops). People of all generations often prefer a hammock to a bed, and tortillas are definitely preferred hechas a mano (made by hand).

Despite the incredible durability of Maya culture, there are certainly signs of change. While some Maya still live in traditional houses, those homes may have multiple televisions and wifi (and many Maya live in completely modern houses with televisions and wifi). While many Maya men still raise bees, or tend milpas (farm plots with the symbiotic crops of beans, squash and corn) as their ancestors did, they might use a cell phone to tell their wives when they’re coming home.

While some changes are inevitable reactions to the modern world, others are more distressing. As I said before, the younger generation often doesn’t speak Maya. The seeds for the milpa crops often come from Monsanto and as such tend to crap out in times of extreme heat, and this, coupled with the disappearance of government subsides, has been forcing farmers to abandon their land. The bees—well you know about what’s been happening to the bees.

The government of our state, Quintana Roo (which comprises most of what was Chan Santa Cruz) seems to be investing more in tourism directed at bringing foreigners to visit the Zona Maya. They’re starting to push my town and the Maya communities that surround it as tourist destinations.

For the sake of putting the modern Maya on the map, I think this is wonderful. But with such things, there’s always the danger that the area could turn into Maya Disneyworld. Since the tourists began arriving in Cancun in the 1970s, much of the land north of my town has turned into an ecological and cultural disaster. That this could happen here breaks my heart.

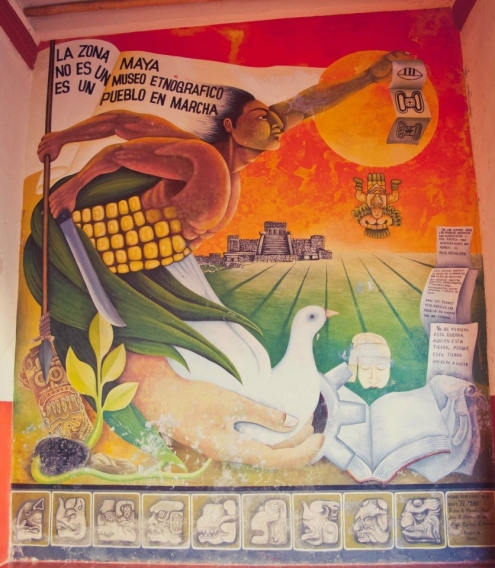

Still, I’m holding out for a happy ending, given the epic, historical resilience of the Maya. My favorite mural in town says “La Zona Maya no es un museo etnographico, es un pueblo en marcha.” It’s a bold statement that translates to “The Maya Zone is not an ethnographic museum, it’s a people on the move.” I hope this statement holds true, that the Maya continue to hold onto a vibrant, breathing culture, evolving with the times but still persisting as the world changes around them.

Hi Molly – Just read your Goodbye Mexico piece 😦 and now this Maya piece :). You may know that two of my daughters are archaeologists working in Belize and studying the ancient Maya. One of them does “community archaeology” which involves current Maya. She started an archaeological field school for high school students in Belize to teach them their history, which has been largely forgotten for all the reasons you mention, plus the British who controlled Belize for a century or so. She’s now director of a non-profit called Inherit which speaks for/with the Maya in Belize and recently won a suit against the Belizean government. The gov’t had held that the Maya were not indigenous to Belize (!!!) and so they government could take their land. Now Inherit will work with the government, the Maya and others (like resort companies) to see that the Maya in Belize are treated fairly. 🙂

I hope I get to meet you one day! I’ve enjoyed your wonderful posts…

Pam Novotny

LikeLike